This is a summarised version of the full report. For the full version, click here.

Summarised report on the survey carried out by Autistic Mutual Aid Society Edinburgh (AMASE), Spring 2018

AMASE is an independent autistic people’s organisation based in Edinburgh. All of the committee are on the autistic spectrum, and our goal is to help autistic people to help make each other’s lives better through peer support, advocacy and education.

Website: www.amase.org.uk Twitter: @amasedin

Authors: Sonny Hallett & Catherine J Crompton

How to cite this report: Hallett, S. & Crompton, C.J. (2018) ‘Too complicated to treat’? Autistic people seeking mental health support in Scotland. Autistic Mutual Aid Society Edinburgh (AMASE) www.amase.org.uk/mhreport

Summary

Autistic people are at high risk of mental health conditions, including depression1, anxiety2, and suicide3. Using a survey, we collected the experiences of autistic people in accessing mental health services in Scotland. Questions focused on challenges faced, what is working well, and what autistic people would like to see done differently. The survey also explored what role the Autism One Stop Shops play in the mental health of autistic people.

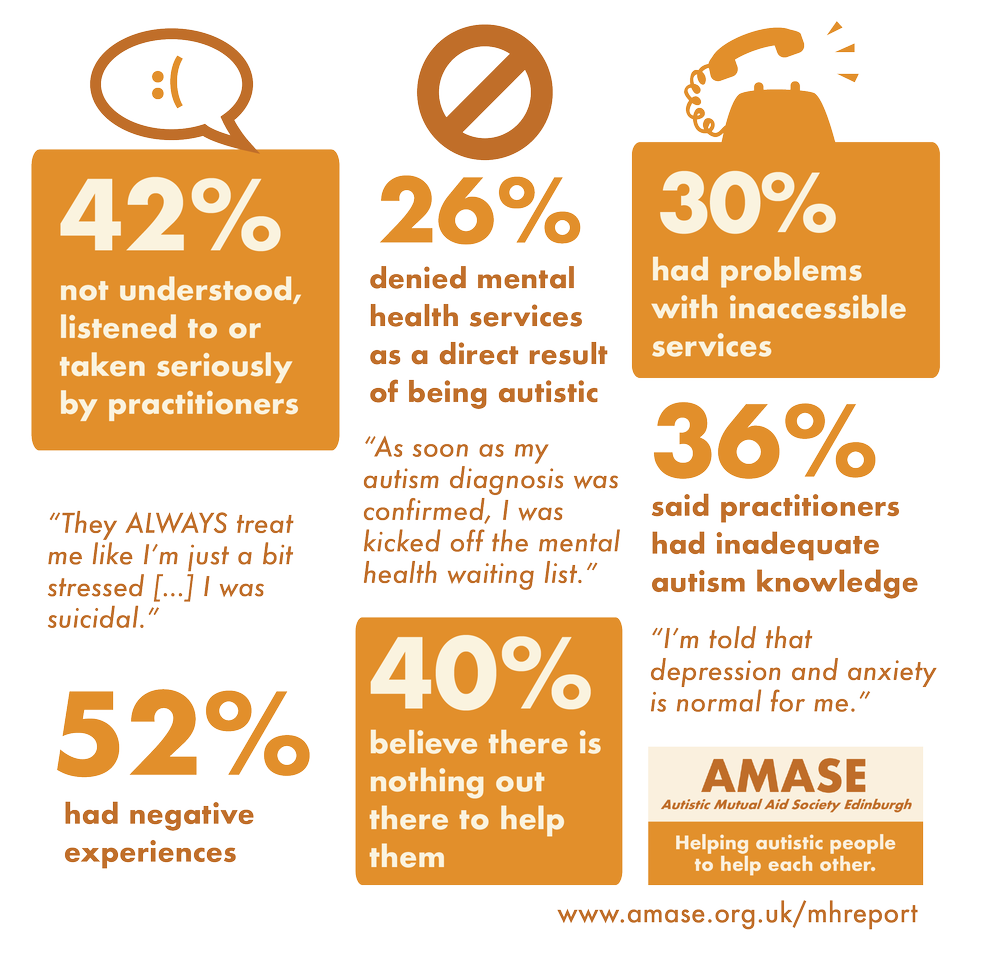

Results suggest that autistic people are being denied access to mental health care as a result of being autistic. Key themes included

- Autistic people being directly denied mental health services due to their autism diagnosis;

- Autistic people not being listened to or taken seriously when they are trying to communicate their mental health distress

- Problems with the basic accessibility of GP surgeries and mental health services

- A lack of understanding of autism and the mental health of autistic people amongst health professionals.

In this report, we describe the findings from this survey, and call for action to address the mental health inequalities faced by autistic people in Scotland.

Alongside these calls to action, we highlight three things that individuals can do immediately to help autistic people.

- Be aware that autistic people experience high rates of mental health problems. Offer support to the autistic people you know or meet.

- If you’re a mental health practitioner and you don’t know much about autism, don’t be afraid to provide treatment. Just ask the autistic person what, if any, adjustments they might need and keep the communication channels open

- Take time to listen to what autistic people have to say about their mental health. You might just listen, but if you have advice, try to offer clear, concrete options in return.

The Survey and Sample

AMASE circulated the survey on Twitter, Facebook, Email, and at a drop-in discussion held in Edinburgh during Spring 2018.

50 autistic individuals across Scotland completed the anonymous online questionnaire. 42% of respondents were based in Edinburgh, 18% in the Lothians, 16% in the Highlands, and the remainder of participants from across Scotland.

Mental Health

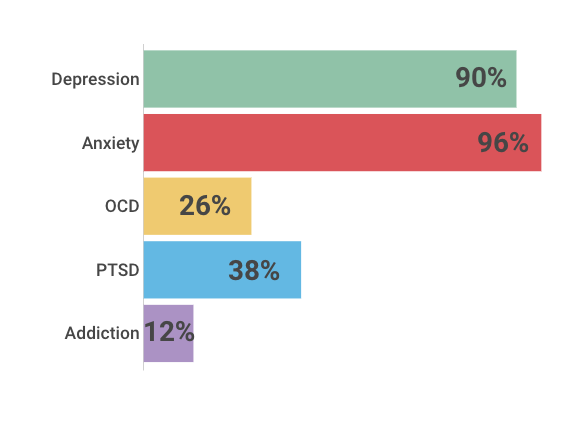

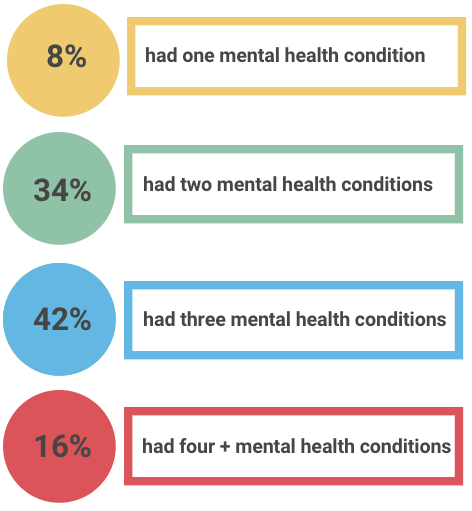

Participants reported high levels of mental health conditions, with all participants having at least one mental health condition, and high rates of comorbidities. Figure 1 describes rates of the most common conditions in our sample; other conditions mentioned included eating disorders, suicidal ideation, borderline personality disorder, psychosis and dissociation. This aligns with previous research suggesting high prevalence rates of mental health conditions in the autistic community1,2,3 though is unusually high, even by the standards of published estimates.

Service use and Experiences

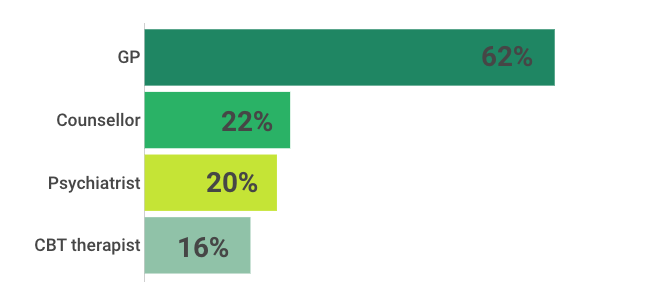

Participants reported accessing a range of mental health services (Figure 2), with only 4% of respondents accessing no mental health services at all, including their GP. More than half of respondents reported overall negative experiences with mental health services, and less than a fifth reported positive experiences (Figure 2).

GPs were the most commonly accessed service for mental health support, acting as an access point for more specific mental health services. Negative experiences with GPs fell into four key themes (Table 1).

| Time | Communicating needs in the short time available ‘The knowledge that an appointment is 10 minutes makes me really anxious… we need more processing time’ |

| Communication and accessibility | A phone-based appointment booking service is not autism-friendly ‘I find making phone calls very difficult. An online booking system may help.’ Doctors’ waiting rooms cause significant sensory discomfort ‘Overstimulation is very common in public waiting rooms for mental health services’ |

| Medication | Medication is the first port of call, with little or no observation or support ‘I was just told “continue to take these medications as the best of a bad bunch” and come back in 12 months’ |

| Lack of listening & understanding | There is a lack of understanding of autism, the autistic experience, and mental health ‘I was so upset [by GP experience]. It took me ages to build up the courage to go back again.’ |

Table 1: Key themes of difficulties when accessing GPs for mental health support.

Autism as a barrier to accessing mental health services

Over a quarter of respondents were denied mental health support and access to mental health services as a direct result of their autism diagnosis. Respondents described being removed from mental health support and services by GPs, mental health teams, and other professionals as soon as their autism diagnosis was confirmed or disclosed.

Several respondents told of professionals describing them as being too complicated or complex for treatment, or that they have the expected amount of mental health distress for an autistic person. According to survey respondents, services with both autism and mental health experience were rarely in evidence.

40% of respondents described being told or feeling that there was nothing at all out there to support them with their mental health problems.

For those who received a referral to mental health services, long waiting times with no intermediary support presented significant problems. Respondents described long waiting times during acute mental health crises and suicidal experiences, and the impact this had on their mental health. While long waiting lists are not uncommon in mental health services, distress may be exacerbated for autistic people due to a failure by services to recognise when they are in crisis.

When finally accessing mental health services, the experience was often negative due to poor knowledge about autism and how this may interact with mental health presentation and treatment (Figure 3). A number of participants stated their mental health deteriorated as a direct result of their experiences with services, and that they would not go back to mental health services in the future.

Autism Understanding

| Incorrect knowledge about autism: many professionals, including psychologists and psychiatrists, had inadequate or incorrect knowledge about autism. They did not understand differences in communication which led to increased anxiety and distress for autistic people, and referrals to inappropriate or unequipped services. “One psychologist dismissed autism as a purely childhood condition” |

| Ignoring autism: often, neurological differences were not taken into account or understood. “I felt like a lot of people ignored my autism” |

| Differences in communicating distress: participants communicated distress to practitioners, but felt they were not listened to and their distress was not taken seriously because it didn’t manifest in the “usual” way. 42% of respondents said their attempts to communicate distress such as depression and thoughts of suicide were not taken seriously or properly acknowledged by professionals. “They ALWAYS treat me like I’m just a bit stressed and I’ll be fine. I was suicidal” “I don’t talk much, I just wish when I did, people listened and realised that since I am speaking, something is up.” |

Figure 3: most common types of autism misconceptions and misunderstandings when accessing services.

One Stop Shops

The Edinburgh, Perth and Highland Autism One Stop Shops are drop-in services for autistic adults, designed to be a safe space that they can go to for social activities with peers. The One Stop Shops are facilitated by staff with expertise in diagnosis, employment, benefits, and housing, and provide support and advocacy. They work with and empower autistic-

led groups (including Autism Rights Group Highland – ARGH) and facilitate peer support. ARGH highlighted in their 2017 Highland One Stop Shop: User Evaluation its impact on the wellbeing of its service users4. Respondents in our survey highlighted the ability of the One Stop Shops to provide the following benefits (Figure 4).

Many respondents described dramatically positive impacts that the One Stop Shops had on their lives. While most of the support described is not mental health specific, the improvement in stability, having a safe space, and access to peers and empathetic allies and mentors has clearly been valuable in improving the respondents’ mental health and general wellbeing.

![“For the first time in my life, I feel that I have a safe and non-judgmental place to go to, with people I trust to talk with, whether I am in crisis, or just have small worries I'd like to prevent from getting bigger, or even for just practical advice on work.”

“Since discovering [the OSS], I have made more progress in my mental health and general stability and wellbeing than I think I ever have.”

“I trust and value the staff for their empathetic skills and understanding of autism”

“They listen to my concerns or need for support and make me feel like a person, my feelings are valid and they will try and support me in the ways they can”](http://4d5b5b7f4141480ab586406d9721d98b.testurl.ws/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/image-7.png)

Other comments about the One Stop Shops focused on anxieties around how the services are structured and issues with accessibility, sometimes relating to the services’ lack of resources or capacity, or their inability to signpost to other more relevant services due to those services not being available. Similarly, there is clear anxiety about the longevity of the One Stop Shops, likely partly due to the Highland One Stop Shop’s continued threats of closure through lack of funding.

The overwhelmingly positive experiences of the One Stop Shops in relation to mental health stand in stark contrast to experiences reported with mental health services and GPs. Feedback on the One Stop Shops repeatedly highlight the value placed by service users on being listened to, understood and empathised with; suggesting the One Stop Shops are providing better mental health support for autistic people than GPs and specific mental health services. The negative experiences above highlight the impact of cuts to valued services; adequate resources to sustain reliable services are crucial.

Conclusions and Recommendations

It is clear the mental health services in Scotland are not fit for purpose for autistic people, and are not providing adequate support to at-risk adults during times of need. Lessons can be learnt from the One Stop Shops, and their contribution to autistic people’s mental health should be better recognised, understood and supported long term. In light of the findings described above, AMASE makes the following calls to action.

- A review of current policy and practice for autistic access to mental health services

Autistic people are denied access to essential mental health support due to their autism diagnosis. This is an unacceptable failure of mental health professionals’ duty of care towards at-risk members of a vulnerable population.

AMASE call for an urgent review of policy and practice for mental health service provision for autistic people, and an identification of the gaps in appropriate service provision across Scotland. We call for a review of accessibility to GP surgeries, and investigation of how they can be made more accessible, including online booking systems.

- Improved autism training and understanding

There is a gulf in communication between autistic patients and service providers. Clear communication can make a huge difference.

AMASE call for a review of training across the NHS and social care providers, with renewed emphasis on communication differences, understanding the autistic experience, empathising with autistic people, and autism and mental health.

We recommend the use of trained intermediaries to bridge the communication gap between autistic patients and professionals, and training led by autistic people with personal or professional experience of mental health difficulties, alongside professionals with extensive experience working with autistic people with mental health conditions. Working with autistic people as equals, listening to their experiences and perspectives is essential to gain understanding and empathy for autistic patients.

- Provide stability for specialist support

The One Stop Shops help autistic people achieve stability in their mental health and wellbeing.

AMASE call for an acknowledgement of the value of the OSSs, and recognition of the gap they are filling in mental health support for autistic people, despite them not being a specific mental health service.

We recommend the existing OSSs funding should be secured indefinitely. We recommend that OSSs are rolled out to other local authorities, and that the OSSs are empowered with resources to take on greater experience in advising on mental health provision and advocating for their service users.

- Create post-diagnostic pathways

Adult autism diagnoses often arise from mental health crises. The lack of post-diagnostic support is problematic.

AMASE recommend a review of the post-diagnostic pathways for adult-diagnosed autistic adults across Scotland. We call for more research into, and awareness of the mental health impacts being undiagnosed until adulthood can have on autistic people, and screening for common mental health conditions as part of the diagnosis process.

We would like to see more exploration of the value of peer support for autistic people and their long-term wellbeing.

- Develop treatment with autistic people in mind

The majority of approaches to mental health care and treatment are developed through testing on non-autistic patients.

AMASE would like to see more research into the impacts and outcomes for conventional mental health therapies and medications on autistic people, and how they can be best adapted to suit people with neurological differences.

- Involve autistic people in planning for change

There should be nothing about us without us. Change must be guided by the voice of people with lived experience.

AMASE emphasises the importance of including and empowering autistic people to take the lead in guiding changes, in line with the Scottish Government’s Delivery Plan for the United Nationals Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities5.

Many of the problems highlighted in this report have stemmed from autistic people not being listened to, taken seriously, or understood. The first step to changing this is to listen to autistic people; believe us when we say there is a problem.

- Rai, D. et al (2018). Association Between Autism Spectrum Disorders With or Without Intellectual Disability and Depression in Young Adulthood. JAMA Network Open, 1(4), e181465-e181465.

- Mattila, M. L. et al.. (2010). Comorbid psychiatric disorders associated with Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism: a community-and clinic-based study. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 40(9), 1080-1093.

- Cassidy, S. et al (2018). Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Molecular autism, 9(1), 42.